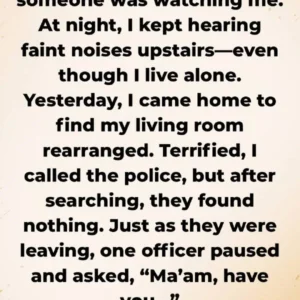

The limousine eased up to the curb in our quiet Midwestern American suburb, and the woman who stepped out was someone my father had spent twelve years convincing me didn’t care whether I lived or died. But here’s what he didn’t know: she didn’t come empty‑handed. And after that night, he would never again tell anyone that this house was his.

Before I go on, if stories about standing up for yourself mean something to you, please hit like and subscribe, and tell me in the comments where you’re watching from right now and what time it is there.

Now let me take you back twelve years, to the day my mother was buried and the day my father started building the cage I’d live in until last Christmas.

I’m nine years old.

The sky is iron gray, the kind of gray that doesn’t promise rain, just nothing. My mother’s casket is mahogany.

I know because my grandmother told me.

“Your mama picked mahogany once for a bookshelf,” she whispers, holding my hand so tight I can feel her pulse. “She had good taste, your mama.”

My grandmother’s name is Vivian Hartwell.

She smells like jasmine and old paper.

At the cemetery, she’s the only person touching me. My father stands six feet away, hands in his coat pockets, jaw locked. He hasn’t cried once—not at the hospital, not at the viewing, not now.

After the last guest leaves, Vivian kneels in front of me.

Her eyes are swollen.

She cups my face and says five words I will carry for twelve years without understanding them.

“I will always find you, little star.”

Then my father steps between us.

“You need to go, Vivian.”

“Richard, she’s my granddaughter. Your daughter is dead because you pushed her too hard.

You’re not welcome here anymore.”

I don’t understand what he means. My mother died of a brain aneurysm.

Nobody pushed anything.

But I’m nine years old and my father is the tallest person in the room, and when he speaks, people stop.

Vivian looks at me over his shoulder. Her lips move, but no sound comes out. Then she turns and walks to her car.

I watch it disappear around the corner.

Within a month, we move.

New town, new number. My father throws out the address book from my mother’s desk drawer.

“It’s just us now,” he says at dinner.

“That’s all we need.”

I believe him. I have no reason not to.

Not yet.

Two years pass.

I’m eleven.

My father brings home Brenda Morris on a Tuesday. She has honey‑blonde hair, a smile that shows all her teeth, and a daughter named Kelsey who is two years older than me.

“This is going to be wonderful,” Brenda says, squeezing my shoulders.

Her nails are acrylic. They dig in.

Within a week, Kelsey moves into my bedroom—the one upstairs with the window seat my mother built.

I’m relocated to the basement.

There’s a cot, a lamp, and a water stain on the ceiling shaped like a fist.

“Kelsey needs sunlight for her skin condition,” Brenda explains.

Kelsey doesn’t have a skin condition. She has a tan from soccer camp.

I learn the rules fast.

I cook breakfast before school. I clean the kitchen after dinner.

I fold laundry on Sundays.

Kelsey picks outfits. Kelsey picks TV shows. Kelsey picks where we eat when we go out, which isn’t often.

And when we do, I sit at the end of the booth.

“Evelyn likes helping,” Brenda tells guests.

“She’s such a little worker bee.”

One evening, I say to my father, “I have homework. Can Kelsey do dishes tonight?”

Brenda’s eyes fill instantly.

She presses a hand to her chest.

“I try so hard, Richard, and she still resents me.”

My father turns to me. His voice is low and final.

“Apologize.

Now.”

I apologize.

I always apologize.

Here’s the thing I won’t learn for another ten years: every single year—every birthday, every Christmas—a package arrives at our old address, then gets forwarded. A gift. A card from my grandmother.

My father signs the “return to sender” slip before I even know it exists.

Every year for twelve years.

But I’ll get to that.

I’m eighteen. I open a letter at the kitchen table and my hands shake.

Full scholarship.

Nursing program. Four‑year university.

Eighty miles east.

I show my father.

He doesn’t look up from his laptop.

“Nurses clean up other people’s messes,” he says. “Just like you do here.”

That same month, Kelsey drops out of community college mid‑semester. My father pays off her tuition balance, her credit card, and buys her a used Audi.

“She’s finding herself,” Brenda says, stroking Kelsey’s hair.

I find myself two part‑time jobs—one at a diner, one at a campus bookstore—and I pay for my own textbooks with quarters and crumpled fives.

I don’t complain.

I’m out of the basement five days a week now. That’s enough.

Then one November night, junior year, I’m home for Thanksgiving.

Everyone’s asleep. I go to the basement to grab a blanket, and behind the water heater I find a box.

Old cardboard.

My mother’s handwriting on the side.

“Margaret, personal.”

Inside, there’s a silk scarf, a half‑used perfume bottle, still faintly sweet, and a photograph. Two women at a party. My mother, young, laughing, and beside her an older woman in a navy dress, arm around my mother’s waist.

On the back, in blue ink: “Margaret and Mom, Vivien’s 60th birthday.”

Vivien.

The name lands like a stone in still water.

My father told me my grandmother died years ago.

“Heart attack before you were born.” But this woman looks healthy, joyful, and the party looks recent. There’s a digital timestamp in the corner: 2001, two years before I was born.

I almost type the name into my phone that night: “Vivien Hartwell.” But my father checks my browser history every Sunday.

I put the photo back. I close the box.

I wait.

Five months later, April.

I come home for Easter weekend. I go straight to the basement. The box is gone.

I find Brenda in the kitchen arranging tulips in a vase.

“The box behind the water heater,” I say.

“Where is it?”

She doesn’t look up.

“Old junk.

I donated it.”

“That was my mother’s.”

“Sweetie, it was collecting dust.”

That night, I can’t sleep. I open Facebook Marketplace on my phone and type in our ZIP code.

I scroll.

And there it is.

My mother’s pearl necklace—the one from the photograph—listed for forty‑three dollars. The seller’s username: B‑Morris‑home.

Brenda’s email handle.

My stomach drops.

I screenshot everything.

The next morning, I find my father in the garage. I show him the listing. I keep my voice even.

“She’s selling Mom’s things.

The necklace.

The scarf. They were in that box.”

He barely glances at my phone.

“Brenda is my wife.

This is her house, too. Drop it.”

“Those were Mom’s.”

“Drop it, Evelyn.”

He goes inside.

The garage door hums shut behind him.

That night in the basement, back on the cot at home, I stare at the water stain and something shifts.

It’s quiet. No thunder, no dramatic realization. Just a slow, terrible clarity.

I always thought keeping quiet was keeping peace.

That absorbing their cruelty was the cost of having a family at all.

That if I was patient enough, kind enough, invisible enough, one day someone would see me.

But lying there in the dark, listening to Brenda laugh at something on TV upstairs, I understand. I wasn’t keeping peace.

I was keeping their comfort.

And nobody was coming to see me.

Not unless I made some noise.

I just didn’t know the noise was already on its way.

December twenty‑first, my father calls a family meeting at the dining table. Brenda sits beside him, pen and notepad ready, like she’s taking minutes for a board.

“We’re hosting Christmas Eve this year,” he says.

“Biggest one yet.

Thirty guests. Neighbors, colleagues from the bank, a few relatives.”

He looks at me the way a foreman looks at a shift schedule.

“Evelyn, you’re on food. I need a full spread.

Ham, sides, two desserts, decorations, table settings.

Start tomorrow.”

I look at Kelsey. She’s painting her nails at the table, not even pretending to listen.

“What’s Kelsey doing?” I ask.

“Kelsey’s helping Brenda with the guest list and outfits.”

“Right.

Outfits.”

I spend the next three days in the kitchen, brining the ham, rolling pie crust at midnight, ironing a tablecloth I find in the back of the linen closet that still smells like my mother’s lavender sachets.

On December twenty‑third, I pause. I look at the Christmas tree in the living room.

It’s enormous.

Brenda insisted on nine feet.

Beneath it, wrapped in gold and silver, are stacks of presents. I count them. Thirty‑two.

I read every tag.

Not a single one says “Evelyn.”

I find Brenda arranging ribbon on the mantle.

“Am I invited as a guest?” I ask.

“Or just staff?”

She laughs. Light, musical, practiced.

“Don’t be dramatic, sweetie.

Family helps family.”

I nod. I go back to the kitchen.

I slice carrots and think about a woman in a navy dress whose name I’m not allowed to search.

Two hundred miles southwest—though I don’t know it yet—a seventy‑eight‑year‑old woman sits in the back of a black sedan on an American interstate, reading a file.

The file contains an address. This address, confirmed seventy‑two hours ago.

She tells the driver, “We go Christmas Eve.”

December twenty‑third, late afternoon, there’s a knock at the side door. Ruth Callaway stands on the porch holding a plate of gingerbread cookies wrapped in cellophane.

She’s our neighbor three houses down, silver hair, reading glasses on a chain.

The kind of woman who remembers everyone’s birthday but never makes a fuss about her own.

She steps into the kitchen and sees me—flour on my cheek, apron stained, alone. She looks at the ham, the pies cooling on the rack, the potatoes still waiting to be peeled.

“All this is you?” she asks.

“Family helps family,” I say.

I mean it to sound normal, but something in my voice cracks.

Ruth sets the cookies down. She glances toward the living room where Brenda’s music is playing, then touches my elbow and steers me out to the back porch.

“Honey,” she says quietly.

“I need to tell you something.

Yesterday, a car was parked out front. Real nice. Black, tinted windows.

Sat there almost an hour.”

I frown.

“Probably lost.”

Cars that nice don’t get lost on Maple Drive.

She pauses, studies my face, then says, softer, “You look just like your mama, you know that?”

My throat tightens.

“Your mama’s mother,” Ruth says carefully.

“She was something else. A force.

You know that, right?”

I open my mouth, but nothing comes out. My father told me my grandmother died.

My father said she didn’t care.

Before I can answer, the back door swings open.

Richard stands there, beer in hand, smile on, eyes sharp.

“Ruth, thanks for the cookies.”

His voice is warm. His gaze is a warning.

Ruth straightens. She pats my arm once.

“Merry Christmas, sweetheart.”

She walks down the porch steps without another word.

She knows something.

But not yet.

Not yet.

Christmas Eve.

The house glows. I’ve been up since five a.m.

The ham is glazed and resting. The mashed potatoes are whipped.

The green bean casserole is golden on top.

Two pies sit on the counter, pecan and apple. I made both from scratch because Brenda said store‑bought sends the wrong message.

By six p.m., guests begin arriving. Coats pile on the bed upstairs.

Perfume and cologne fog the hallway.

Thirty people fill the living room, champagne flutes catching the light from the nine‑foot tree.

I’m in the kitchen, apron on, hair pinned back, plating appetizers.

From the living room, I hear my father’s voice rise over the chatter.

“And this is my eldest, Kelsey. She’s been such a blessing to this family.”

I peer through the kitchen doorway.

Kelsey stands by the tree in a red velvet dress, smiling like she’s accepting an award. Brenda beams beside her.

A woman I recognize—Mrs.

Palmer from church—glances around.

“And where’s your other daughter, Richard?”

My father waves a hand.

“Oh, Evelyn’s helping out in the kitchen.

She likes to stay busy.”

Mrs. Palmer tilts her head.

“Helping out on Christmas Eve?”

“She insisted,” Brenda says smoothly. “She’s selfless like that.”

No one follows up.

No one checks.

I stand in the kitchen doorway holding a tray of bruschetta I spent two hours making.

My name hasn’t been spoken once tonight except as a footnote. I look at the living room—the laughter, the warmth, the tree, the gifts—and I realize something very simple.

I’m not part of this family.

I’m the machine that keeps it running.

I set the tray down. I untie my apron.

I put on the one nice sweater I own, navy blue, cable knit, the only thing in my closet that isn’t stained.

I walk into the living room.

I sit at the end of the dining table. There’s no place card for me, so I pull up a folding chair between two of my father’s colleagues from the bank. One of them, a man named Gary, nods politely.

The other doesn’t notice I’m there.

The table is beautiful.

I know because I set it. The cloth napkins, the candles, the centerpiece I made from pine branches and cinnamon sticks at one in the morning.

I eat in silence for ten minutes.

Then Kelsey opens the first gift. Then another.

Then Brenda opens one.

Then a neighbor couple exchanges small boxes.

The pile under the tree shrinks. Name after name called. Laughter, thank yous.

Wrapping paper crinkling.

I sit still, waiting.

The pile gets smaller.

My name never comes.

Finally, when the last ribbon is pulled, I speak. I don’t shout.

I don’t whine. I keep my voice at room temperature.

“Dad, is there one of those for me?”

The room doesn’t go silent all at once.

It goes silent in waves, conversation dying table by table like candles blown out in sequence.

Brenda reacts first.

Her eyes go red instantly. Her lip quivers.

“Evelyn, this isn’t the time.”

“I’m just asking.”

My father sets down his glass.

“We talked about this. You’re twenty‑one.

Kelsey is twenty‑three.”

“She has six,” I say.

Nobody moves.

I can hear the clock in the hallway.

Brenda turns to Richard, tears streaming. Her hand finds his arm.

“She always does this,” Brenda whispers, but the room is so quiet everyone hears.

What happens next takes eleven seconds.

I’ve replayed it enough times to count.

Second one, Richard pushes his chair back.

Second three, he grabs my upper arm. His fingers press into bone.

Second five, he walks me to the front door.

My heels drag on the hardwood I mopped yesterday.

Second eight, he opens the door.

The cold hits like a wall, a negative‑twelve‑degree wind. Snow comes down sideways.

Second nine, he pushes me onto the porch. I stumble.

I’m wearing socks, no shoes.

The snow soaks through instantly.

Second eleven, the door shuts. The deadbolt clicks.

I stand there.

The porch light is off. The only glow comes from the windows, warm and golden and full of people.

I press my hand to the glass.

Inside, my father straightens his shirt, returns to the table, and picks up his champagne.

Brenda dabs her eyes. Somebody pats her back.

“You want to talk back?” he’d said as he shoved me through the door. “Do it outside.

Come back in when you learn some respect.”

My feet burn, then sting, then go numb.

I curl my toes, but I can’t feel them anymore. My sweater is thin.

Wind cuts through cable knit like it isn’t there. My fingers turn white.

Ten minutes.

The party resumes inside.

Laughter again. Music. Someone found the Bluetooth speaker.

Twenty minutes.

Snow reaches my ankles.

I crouch against the railing and hug my knees.

I look through the window one more time. Kelsey stands by the tree holding a phone.

She spots me, walks to the glass, smiles, and waves her fingers slowly the way you’d wave to a stranger’s dog. Then she pulls the curtain shut.

I close my eyes.

I honestly believe I might not make it through this night, outside my father’s door on Christmas Eve.

I need to pause here for a second, because what happens next I still can’t talk about without my hands shaking.

But before I continue, if you’ve ever been punished for simply asking a fair question, type “I’ve been there” in the comments. Or if you think I should have fought back right then, type “fight back.” Let me know.

Okay. Here’s what happened next.

The snow is patient.

It doesn’t rush.

It just keeps falling, keeps layering, keeps pressing its weight onto everything beneath it—my shoulders, my knees, the tops of my soaked socks.

I don’t know how long I’ve been out here. Maybe twenty‑five minutes, maybe thirty.

Time moves differently when your body starts shutting down the non‑essentials—fingers, then ears, then the part of your brain that tells you to keep trying.

I think about my mother. Not in a grand cinematic way.

I just remember her hands.

The way she’d warm mine between hers after I walked home from the bus stop in January. She’d blow on my knuckles and say, “There you go, little star. Good as new, little star.”

I whisper it now to nobody.

“Mom, I don’t know what to do.”

The wind answers.

The house doesn’t.

But then—movement.

Through the side window, I see a figure. Ruth Callaway.

She’s standing near the curtain, peering out. Her face is tight.

She turns and says something to my father.

I can’t hear the words through the glass, but I see his hand—a sharp, dismissive wave. The kind of wave that means not your business.

Ruth stares at him for a long moment, then she turns away.

I pull my knees tighter. My jaw won’t stop trembling.

Then I think about the photograph.

The one in the cardboard box.

Two women. A birthday party.

“Margaret and Mom. Vivien’s 60th birthday.”

Ruth’s words from two days ago: “Your mama’s mother.

She was something else.”

My father said she died.

But the photo said otherwise. Ruth’s voice said otherwise.

What if the story I’d been told my whole life—that my grandmother abandoned me, forgot me, didn’t want me—was the lie that kept me in this cage?

I press my frozen palms together. And for the first time, I don’t pray for the door to open.

I pray for something else entirely.

Through the window, the party continues like I never existed.

My father stands at the head of the table. I can see his mouth moving, can read the shape of his words through the frosted glass.

He raises his champagne flute.

The room listens.

“I apologize for the disruption,” he says.

I can just make it out through the thin pane near the front door.

“Evelyn has been struggling. We’ve tried everything.

Brenda has been a saint.”

Brenda lowers her head—humble, wounded, a careful performance.

“I just want her to be happy,” she says.

Two women at the table reach over to squeeze her hand.

Kelsey chimes in from the couch.

“She literally screamed at Mom last week.”

That’s not true.

Last week I said, “Please don’t sell Mom’s things.” I didn’t raise my voice.

I never raise my voice. Raising my voice is what gets you locked outside.

A few guests murmur. Heads nod.

The narrative is set.

Poor Richard. Patient Brenda.

Troubled Evelyn.

I watch it all through six inches of glass and twelve years of silence.

But I also see Ruth.

She doesn’t nod. She doesn’t murmur.

She sets her glass on the end table, picks up her coat from the chair, and walks toward the back of the house—not toward the front door where I am, toward the back.

Thirty seconds later, the side gate creaks.

Footsteps crunch in the snow. And then Ruth is beside me, draping a wool blanket over my shoulders.

It’s warm. It smells like cedar.

“Here, sweetheart.” Her voice is steady, urgent.

“I called someone.”

My teeth chatter so hard I can barely speak.

“Who?”

Ruth looks at me.

Her eyes are full of something I haven’t seen directed at me in twelve years: certainty.

“Someone who should have been here a long time ago.”

Somewhere down the street, I hear an engine. Low, heavy, getting closer.

The front door swings open.

Light and warmth spill onto the porch for exactly two seconds before my father’s body fills the frame. He sees Ruth.

He sees the blanket around my shoulders.

His nostrils flare.

“Ruth. This is a family matter.”

Ruth doesn’t flinch. She’s sixty years old and four inches shorter than him, but she stands like a woman who’s been waiting to say something for a very long time.

“A family matter?” She gestures at my feet.

“She’s barefoot in the snow, Richard.”

“She’s being taught a lesson.

Go back inside or go home.”

“Is that what you call this? A lesson?”

“I call it parenting.”

Ruth’s chin lifts.

“Margaret would be ashamed of you.”

The name lands like a slap.

My father’s face goes white, then red, in the space of a breath. He opens his mouth, closes it, opens it again.

“You don’t get to say her name.”

“Somebody has to, because you buried it along with everything else.”

Ruth holds his stare for three full seconds.

Then she turns, walks down the porch steps, and stands at the edge of the driveway.

Not leaving. Waiting.

My father looks at me. I’m clutching the blanket around my shoulders.

My lips are blue.

He reaches down and yanks the blanket away. The cold crashes back in.

“You don’t get sympathy,” he says.

“You earn your place.”

Something in me shifts. Small, structural, like a crack in a foundation you don’t notice until the wall starts leaning.

“Earn my place,” I say.

My voice is quiet, but it doesn’t shake.

“In a house my mother lived in.”

He flinches, just for a second. A micro‑expression. There and gone.

But I see it.

Then the door slams shut.

The deadbolt turns. I’m alone in the snow again.

But not for long.

He doesn’t waste time.

Through the window, I watch my father return to the living room, smooth his shirt, and pick up the room like a conductor picks up an orchestra.

“I need to be honest with all of you,” he says.

He pauses. The guests lean in.

He has their attention.

He always does.

Richard Dawson, branch manager at First Heritage Bank, three‑time Rotary Club president, the man who hosts the best parties on Maple Drive. When he speaks, people listen.

That’s how control works. You build the stage long before you need it.

“Evelyn has had behavioral problems since she was a child.

Her mother coddled her.

Brenda and I have tried our best, but tonight you all saw she’s having a hard time. We even offered to pay for therapy.

She refused.”

That’s not true. Nobody ever offered me therapy.

Nobody ever offered me anything except a cot in the basement and a list of chores.

“She’s been getting worse,” Kelsey says from the couch.

“Last week she was screaming.”

Three lies in thirty seconds. A family record.

A couple near the fireplace whispers to each other. Gary from the bank stares at his hands.

Mrs.

Palmer frowns but says nothing.

I stand outside in the snow, hearing all of it through the thin wall near the front door—every word, every nod, every silence that means agreement.

Tears run down my face, but they’re half‑frozen before they reach my jaw. I want to scream.

I want to pound on the glass and say, I cooked your food. I decorated your tree.

I ironed your tablecloth.

And you locked me out for asking a question.

But I don’t. I stand still and I wait, because down the road headlights are turning onto Maple Drive.

Eleven fourteen p.m. I’ll never forget the time because Ruth checks her watch and whispers it from the edge of the driveway.

“Eleven fourteen.”

The headlights are wide and low.

They sweep across the snow‑covered lawns of Maple Drive like searchlights, turning the white ground pale gold.

The engine is quiet—the expensive kind of quiet. And the car that emerges from the dark is long and black and polished to a mirror shine.

A limousine, on Maple Drive, on Christmas Eve, in front of my father’s house.

It glides to the curb and stops.

The engine idles. Snow drifts against its tires.

Ruth walks to the car.

She bends toward the rear window and nods at whoever’s inside.

The driver’s door opens.

A man in a dark coat steps out, circles to the rear passenger side, and opens the door.

Another man emerges first, middle‑aged, gray overcoat, leather briefcase in his left hand. He looks at the house, then at me, then back at the car.

Then a hand appears on the doorframe—thin, steady. A single gold ring on the fourth finger.

A woman steps out.

She’s seventy‑eight years old, but she moves like someone who has never once waited for permission.

White cashmere coat, silver hair pinned in a low knot, eyes sharp and dark and wet.

She sees me. I’m crouching on the porch, socks soaked through, lips blue, sweater crusted with snow, shaking so hard my teeth click like a metronome.

She stops walking.

Her hand goes to her mouth. Her chest rises once, hard, like she’s swallowing something jagged.

Then she crosses the yard in five steps, unbuttons her coat, and drapes it over my shoulders.

It’s warm.

It smells like jasmine.

She cups my face in both hands. Her palms are soft and dry and burning warm.

She says two words.

“Little star.”

I know her. Not from memory.

From a photograph hidden behind a water heater in a basement.

Two women at a birthday party, one of them laughing, one of them holding her daughter like she’d never let go.

“I know you,” I whisper. “From the photo.”

Her eyes close.

When they open, they’re red and fierce and full of something that has been building for twelve years.

“I know you, too, little star. I’ve been looking for you.”

She pulls me into her arms.

I’m frozen and shaking and I smell like ham glaze and snow, and she holds me like none of that matters, like I’m the only warm thing in the world.

Then she straightens.

She looks at the house, the golden windows, the laughter inside, the nine‑foot tree, the thirty guests, and the man who locked his daughter outside in the cold.

She turns to the man with the briefcase.

“Douglas.”

He nods once, opens the briefcase.

Vivian walks to the front door. She doesn’t knock gently. She knocks three times—firm, measured, final.

The door opens.

My father stands in the frame, champagne in his hand, smile half‑formed.

Then he sees her.

The glass tilts.

Champagne spills on his wrist. He doesn’t notice.

“Vivian.”

Her name comes out of his mouth like a bone stuck in his throat.

She doesn’t greet him.

She looks past his shoulder—at the thirty faces turned toward the door, at Brenda frozen mid‑laugh on the couch, at Kelsey holding a gift bag.

Then she looks back at me, still wrapped in her coat on the porch, and back at him.

“You locked my granddaughter in the snow,” she says. Her voice carries.

“On Christmas Eve.

In the house I bought.”

Thirty people go silent at once.

Brenda stands up from the couch.

“Who is this woman?”

Nobody answers her. Every pair of eyes is locked on the doorway, on the seventy‑eight‑year‑old woman in a white blouse who just said the word “bought” like she was reading a verdict.

My father recovers first. He always does.

“Mother, this is a misunderstanding—”

“I am not your mother.” Vivian’s voice is a scalpel—clean, precise.

“I am Margaret’s mother.

And this is not your house.”

Douglas steps inside. He moves with the practiced calm of a man who has delivered uncomfortable truths in far more hostile rooms than this.

He opens the briefcase on the dining table, right next to the centerpiece I made, and removes a folder.

“This property,” Vivian says, lifting a document for the room to see. “Forty‑seven Maple Drive, was purchased by me, Vivian Hartwell, in 2003 as a wedding gift for my daughter Margaret.

The deed is in my name.

It has always been in my name.”

Richard shakes his head.

“That’s not— I’ve been paying—”

“You’ve been living here rent‑free for twenty‑one years.” Vivian doesn’t raise her voice. She lowers it, which somehow lands even harder. “I allowed it for Margaret’s sake.

And then for Evelyn’s.”

The room shifts.

I can see it—the way people’s postures change, the way Gary from the bank uncrosses his arms, the way Mrs. Palmer puts her hand over her mouth.

Brenda’s face cycles through three expressions in two seconds: confusion, fury, calculation.

“Richard, what is she talking about?

This is your house. You pay the bills—utilities, maintenance—”

“Paying the electric bill doesn’t make you the owner, Richard,” Vivian says.

Douglas sets the deed on the table.

Then a second document.

Then a third. Then a thick stack of envelopes bound with a rubber band.

“Twelve years of certified letters,” he says mildly. “All returned unopened.”

Vivian turns to me.

I’m standing just inside the doorway now.

Douglas guided me in out of the cold—“Please, miss”—and draped a blanket from the car over my legs. My feet are on the warm hardwood.

They sting, coming back to life.

“Evelyn.” Vivian’s voice changes. The scalpel becomes a hand.

“Your grandfather and I wrote to you every birthday, every Christmas.

Cards, gifts, letters, for twelve years.”

The room holds its breath.

I look at my father.

“Is that true?”

He doesn’t answer. He’s staring at the stack of envelopes on the table like they’re a grenade with the pin pulled.

“Dad, did you send her letters back?”

“She’s manipulating you,” he says. His voice cracks at the seam.

“Just like she manipulated your mother.”

“That’s not true, Richard.”

Ruth again.

She’s standing in the back doorway, coat on, arms crossed. I don’t know when she came in, but she’s here.

“Margaret loved her mother,” Ruth says.

“More than anything. You were the one who cut Vivian off.

I was there.

I watched it happen.”

My father opens his mouth. Nothing comes out.

“One hundred forty‑four letters,” Vivian says. She picks up the bundle and holds it where the light catches it.

Every envelope is addressed in the same handwriting.

Every one is stamped “Return to sender.” Not one reached her.

A woman near the fireplace gasps. Gary from the bank pushes his chair back and stands, as though sitting at this table suddenly implicates him.

Kelsey looks at Richard.

“Dad, what’s going on?”

Brenda is already moving.

She takes two quiet steps toward the staircase like a woman calculating the fastest route to the exit.

My father stands in the middle of his own living room, surrounded by his guests, his decorations, his champagne, and he has nothing left to say.

The cage is open.

One hundred forty‑four letters. Can you imagine that?

Twelve years of birthday cards, Christmas gifts, handwritten notes, all intercepted, all sent back.

If this story is hitting you somewhere deep, please share it with someone who needs to hear it today.

And tell me in the comments—would you forgive Richard, or would you walk away? Let me know.

Let’s keep going, because Vivian wasn’t done.

Vivian lets the silence do its work. She doesn’t rush.

She spent twelve years waiting.

Another thirty seconds is nothing.

Then she speaks, and she speaks to Richard the way you speak to someone who has already lost but doesn’t know it yet.

“I gave you this house for Margaret. Margaret is gone.” She pauses.

“And you used it as a cage for her daughter.”

Richard’s jaw works. His fists clench at his sides.

But there’s nowhere to swing.

Not with thirty witnesses. Not with a lawyer holding a deed. Not with his daughter’s frozen socks leaving wet prints on his hardwood.

“Effective January fifteenth,” Vivian says, “I am reclaiming this property.

You have three weeks to vacate.”

“You can’t do that.”

Douglas doesn’t look up from the folder.

“She can.

She’s the legal owner. You have no lease, no contract, no claim.

I’ll file the formal notice tomorrow morning.”

Richard turns in a slow circle, scanning the room for an ally. Gary looks at the floor.

Mrs.

Palmer looks at her lap. The couple near the fireplace is already reaching for their coats. Nobody meets his eyes.

Then Brenda’s voice cuts through, and it’s a voice I’ve never heard before.

Not the soft, wounded tremor she uses on Richard.

Something harder, colder. Real.

“Richard.”

She’s standing at the foot of the stairs, purse already on her shoulder.

“You told me this was your house.”

“It is my—”

“You told me this was yours.”

The mask falls.

Brenda isn’t crying now. She’s calculating, and the math just changed.

Vivian watches the exchange without expression.

Then she turns to Brenda.

“And you.

I know about the necklace. Margaret’s pearl necklace. I know you sold it online for forty‑three dollars.”

Brenda’s face drains of color so fast I can see it from across the room.

The cage isn’t just open.

It’s demolished.

My father tries one last thing—the only tool he has left when authority fails: sentiment.

He turns to me.

His eyes soften. His shoulders drop.

His voice goes quiet, almost tender. And if you didn’t know him—if you hadn’t spent twenty‑one years studying every shift in his tone, the way a sailor studies wind—you might believe it.

“Evelyn, sweetheart.” He takes a step toward me.

“You’re my daughter.

Don’t let this woman come between us. I was just… I lost my temper. It’s Christmas.

Let’s not do this.”

I look at him.

I look at the door he pushed me through. I look at the deadbolt he turned.

I look at the window Kelsey waved from before pulling the curtain shut. I look at the thirty guests who sat in silence while I stood barefoot in the snow.

I don’t shout.

I don’t cry.

I speak the way you speak when you finally find the floor after years of falling.

“You locked me outside at negative twelve degrees, barefoot, on Christmas Eve, and went back to your wine. That wasn’t ‘I lost my temper.’”

He opens his mouth.

“You didn’t lose your temper,” I say. “You made a choice.

Just like you chose to hide every letter Grandma sent.

Just like you chose to tell me she abandoned me for twelve years.”

He opens his mouth again. I don’t let him fill it.

“I’m not punishing you, Dad.

I’m done waiting outside your door.”

I turn to Vivian. She extends her hand.

I take it.

We walk toward the front door.

Ruth Callaway follows. Douglas gathers the documents and closes his briefcase with a soft click.

Thirty people watch us leave. Nobody speaks.

The Christmas tree blinks red and gold behind us, lighting up a room full of people who will never look at Richard Dawson the same way again.

I don’t look back.

The limousine is warm.

Not house‑warm. Not blanket‑warm.

The kind of warm that seeps into your bones and tells your body it’s safe now. You can stop clenching.

Vivian sits beside me.

She tucks a second blanket around my legs, then reaches over and takes my frozen hands between hers.

She doesn’t rub them. She just holds them steady and firm, the way she must have held my mother’s hands once.

“I looked for you every single day, little star.”

My voice is a wreck.

“He said you didn’t want me.”

“I wanted you so much I hired three investigators,” she says. “The first two hit dead ends.

Your father moved twice, changed phone numbers, used Brenda’s name on every bill.” She squeezes my hands.

“The third one found this address seventy‑two hours ago. I was on a plane the next morning.”

“You came for Christmas.”

“I came for you.

Christmas was just the clock.”

I break. Not the way I broke in the basement, silent and swallowed.

I break the way you break when someone finally holds the door open after you’ve been knocking your whole life—loud, messy, shaking.

Twelve years of silence come out in ninety seconds.

Vivian doesn’t shush me.

She doesn’t pat my back and tell me it’s okay. She just holds on.

When I finally stop, I look out the rear window. The house is shrinking.

The Christmas lights blink against the snow.

Inside that house, my father is standing in front of thirty people who just learned that his home isn’t his, his story isn’t true, and his daughter—the one he locked outside—walked away on her own terms.

I press my forehead to the cold glass.

“Merry Christmas, Mom,” I whisper.

The limousine turns the corner.

Maple Drive disappears.

And for the first time in twelve years, I’m not cold.

The fallout is not dramatic. It’s administrative.

Which, if you think about it, is worse.

The week after Christmas, the story travels the way stories do in small American towns—not through headlines, but through coffee shops, church lobbies, and bank lines. Thirty guests means thirty households.

Thirty households means a hundred conversations before New Year’s.

I learn the details later, mostly from Ruth.

December twenty‑eighth, Brenda packs two suitcases and leaves with Kelsey while Richard is at work.

She doesn’t file for divorce. She doesn’t leave a note. She just goes.

When the foundation you built your life on turns out to belong to someone else, there’s nothing left to argue about.

January second, Richard returns to the bank after the holiday break.

His manager calls him into the office within the hour.

“Richard, some clients have raised concerns. There are questions about your integrity.”

He isn’t fired.

Not yet. But he’s watched, monitored.

The kind of professional limbo where every handshake now carries a footnote.

January fourth, Gary—the colleague from the party—transfers his accounts to a different branch.

He doesn’t explain. He doesn’t have to.

January fifteenth, Douglas files the formal notice. Richard has seventy‑two hours to confirm his move‑out date.

He doesn’t contest it.

There’s nothing to contest. The deed has never had his name on it.

Richard calls me fourteen times that month.

I don’t pick up. Not because I’m full of rage.

I just don’t have the bandwidth for anger.

I’m too busy learning what it feels like to live without a cage.

His final attempt comes through Douglas in a sealed envelope.

“Please tell Evelyn I’m sorry.”

I read it at Vivian’s kitchen table. I fold it once. I set it down.

I don’t reply.

Some apologies aren’t invitations.

They’re exits. And I’m not obligated to hold the door.

Vivian’s house sits on a hill outside a town called Whitfield, about forty minutes from the nearest highway.

It’s not a mansion. It’s a craftsman—wide porch, green shutters, a garden that sleeps under snow right now but will, I’m told, explode with peonies in May.

She gives me the upstairs bedroom, south‑facing, two windows, sunlight so warm it wakes me without an alarm.

It’s the first time since I was nine that I’ve slept above ground.

On my third morning, Vivian sets a box on the kitchen table.

It’s large, heavy.

The cardboard is reinforced at the corners and the top is sealed with packing tape that’s been opened and resealed many times.

“These are yours,” she says. “They’ve always been yours.”

Inside, there are one hundred forty‑four envelopes sorted by year. Each one is addressed to me in the same handwriting, steady and deliberate and full of love.

I open the first one, dated March fifteenth, twelve years ago.

My tenth birthday.

“Dear little star, I don’t know if you’ll ever read this, but I want you to know that on this day, someone in this world celebrated you.

I baked a small cake—vanilla, your favorite, your mother told me once. I blew out the candle for you.

I wished you were safe. I wished you were warm.

I wished you knew.

All my love, Grandma V.”

I read it three times.

Then I open the next one. And the next.

Birthday cards. Christmas letters.

Notes written on hotel stationery from places she traveled.

A drawing of a star she made on a napkin and tucked inside the envelope for my eighteenth birthday. A folded letter from a financial advisor confirming a college fund opened in my name, fully funded, untouched.

My father hid that, too.

I sit in Vivian’s kitchen and read every letter, all one hundred forty‑four.

It takes me four hours. She sits across from me the whole time.

She doesn’t say a word.

She’s just there.

February. I finish my last semester of nursing school. The commute from Vivian’s house is longer, but she insists on driving me to the bus station every morning.

“I have twelve years of driving to make up for,” she says, adjusting her mirror.

“Let me have this.”

Graduation day is small and bright.

I walk across the stage in a white dress I bought with money from my campus bookstore job. When I look into the audience, Vivian is in the second row, upright as a cathedral, clapping with both hands.

Ruth Callaway is beside her. She drove ninety minutes to be there.

On the ride home, the highway is silver with late‑winter sun.

I watch the trees blur past and ask the question I’ve been turning over for weeks.

“Grandma, do you think I should forgive him?”

Vivian doesn’t answer right away.

She drives for a full mile in silence.

“Forgiveness is yours to give, not his to demand,” she says at last. “And you don’t have to decide today.”

I think about that. I think about the deadbolt clicking, the champagne poured while I froze, the letters hidden in a drawer I never knew existed.

I think about the man in the garage who said, “Drop it, Evelyn.”

“I don’t hate him,” I say finally.

“I just don’t trust him. Maybe that’s enough for now.”

Vivian glances at me.

“That’s more than enough.”

That night, I write a letter.

It takes me twenty minutes. I give it to Douglas the next morning to forward.

“Dad, I hope you find peace.

But I need mine first.

Please don’t contact me again until I reach out. If I reach out. That’s my choice now.

Evelyn.”

Four sentences.

No anger, no punishment. Just a line drawn in clean sand.

Some doors close quietly.

That doesn’t make them any less shut.

I want to talk to you for a minute. Not as a character in a story—as the person who lived it.

I’m not telling you this so you’ll hate my father.

I’m telling you this so that if you’re standing outside someone’s door right now—in the snow, in the silence, in whatever cold they’ve locked you in—you know that the door isn’t the only way forward.

For twelve years, I thought peace meant keeping quiet, absorbing the hurt, smiling through the exclusion, telling myself that if I was just good enough, patient enough, invisible enough, they’d eventually see me.

Let me in. Make room.

They didn’t.

And here’s what I’ve learned since: silence isn’t peace. Silence is the price you pay for someone else’s comfort.

And when the cost of staying quiet is your own dignity, that’s not loyalty.

That’s erasing yourself.

My grandmother taught me something I’ll carry forever. She said, “You don’t need anyone’s permission to have value, but you do need to give yourself permission to walk away.”

I walked away.

Not in anger, not in revenge. I walked away because I finally understood that love doesn’t lock you out.

Love drives two hundred miles on Christmas Eve in a snowstorm because it heard you might be cold.

Today, I work at a hospital about thirty minutes from Vivian’s house.

I’m a registered nurse. I help people feel safe in their worst moments, and I think I’m good at it. Maybe because I know what it feels like when nobody comes.

I have a small apartment now, close enough to visit Vivian every weekend.

I have a cat named Star.

She sleeps on my chest every night and doesn’t care whether I earned my place. I already have one.

I always did.

This Christmas is different.

Vivian’s craftsman house smells like cinnamon and pine. The tree is small—five feet, maybe—and we decorated it together.

No nine‑foot statement piece.

No thirty guests. No gold wrapping paper piled in towers.

Just us.

Two place settings. Two mugs of cocoa.

A fire in the hearth.

Snow falling outside the window, soft and steady. And for the first time in my life, I’m watching it from the warm side of the glass.

Under the tree, two gifts.

“Open yours first,” Vivian says.

I pick up the small box.

I unwrap it carefully. Inside, on a bed of velvet, is a pearl necklace.

A pendant hangs from the center, a tiny oval locket.

I press the clasp.

It opens.

Inside, a photograph. My mother, young, laughing. The same photo from the cardboard box in the basement, but smaller, miniature, perfectly preserved.

“How did you—?”

“The original was sold,” Vivian says softly.

“I had the same jeweler make it from a photo your mother gave me thirty years ago.” Her eyes shine, but her voice is steady.

“Brenda can sell a necklace. She can’t sell a memory.”

I fasten it around my neck.

The pearl rests just below my collarbone. Cool at first, then warm.

I look out the window.

Snow falls on the porch, but the porch is empty.

No one is shivering. No one is locked out. No one is watching happiness through a window, wondering why it never includes them.

Last Christmas, I stood outside in the snow, barefoot and frozen, watching someone else’s joy through a pane of glass.

This Christmas, I am the warmth inside.

I press the locket against my chest.

I close my eyes.

“Merry Christmas, little star,” Vivian says.

“Merry Christmas, Grandma.”

That’s my story.

And now I want to hear yours.

If you’ve ever had to walk away from someone you love to protect yourself, type “I walked away” in the comments. Or if you chose to stay and fight for your boundaries, type “I stayed and fought.” Both are brave.

Both are valid.

If this story moved you, check the description for more stories just like this one. Thank you for being here.

Merry Christmas, little stars.